Introduction

Language Evolution

We are not sure which was the first language ever spoken in our world. Was there even one primordial language, or were there several that spontaneously appeared around our world here and there? We cannot know for certain, this is too far back in our history. Some scientists estimate the firsts of our kind to be gifted the ability to speak lived some hundred of thousand of years back, maybe twice this period even. There is absolutely no way to know what happened at that time with non-physical activities, and we can only guess. We can better guess how they lived, and how they died, than how they interacted with each other, what was their social interaction like, and what were the first words ever spoken on our planet. Maybe they began as grunts of different pitches, with hand gestures, then two vowels became distinct, a couple of consonants, and the first languages sprung from that. This, we do not know, and this is not the subject of this book anyways.

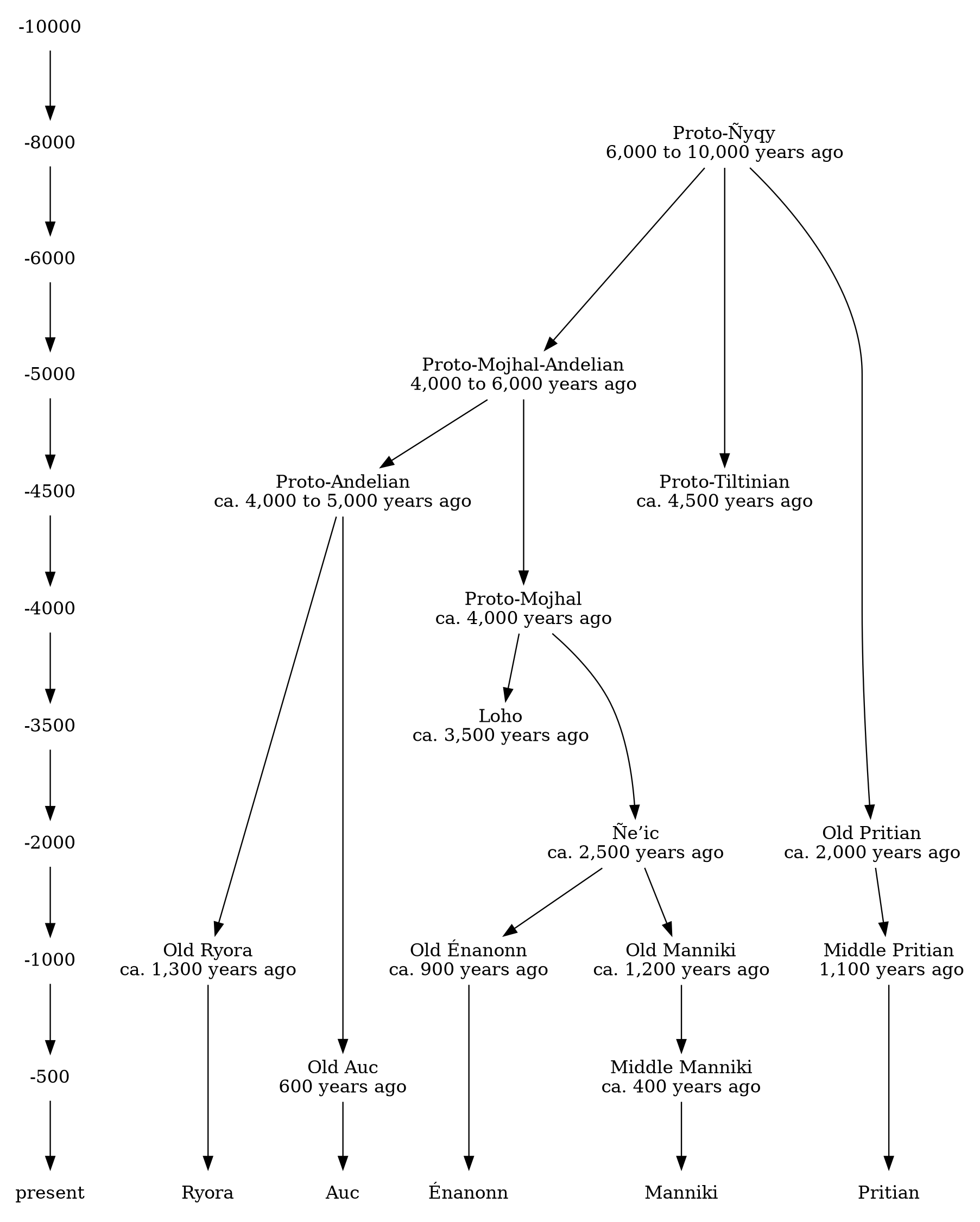

What we do know is, languages evolve as time passes. One language can morph in the way it is pronounced, in the way some words are used, in the way they are shaped by their position and role in the sentence, by how they are organized with each other. A language spoken two centuries back will sound like its decendent today, but with a noticeable difference. Jumping a couple of centuries back, and we lost some intelligibility, and some sentences sound alien to us. A millenium back, and while the language resonates, we cannot understand it anymore. Going the other way around, travelling to the future, would have the same effect, except that we would not necessarily follow only one language, but several, for in different places, different changes would take place. As time goes by, these differences become more and more proeminent, and what was once the same langage becomes several dialects that become less and less similar to one another, until we end up with several languages, sister between themselves, daughters to the initial language.

Relating Languages Between Themselves

We are not sure who first emited the theory of language evolution; this has been lost to time during the great collapse two thousand years back, and only a fraction of the knowledge from back then survived the flow of time. We’re lucky even to know about this. It’s the Professor Loqbrekh who, in 3489, first deciphered some books that were found two decades prior, written in Énanonn. They described the principle of language evolution, and how language families could be reconstructed, how we could know languages are related, and a hint on how mother languages we do not know could be reconstructed. The principle on how historical linguistics are the following:

If two languages share a great number of coincidentally similar features, especially in their grammar, so much so that it cannot be explained by chance only, then these two languages are surely related.

By this process, we can recreate family trees of languages. Some are more closely related to one another than some other, which are more distant. Sometimes, it is even unsure if a language is related to a language tree; maybe the language simply borrowed a good amount of vocabulary from another language that we either now of, or died since.

The best attested languages are the ones we have written record of. In a sense, we are lucky: while we do know a vast majority of the written documents prior to the great collapse were lost during this sad event, we still have a good amount of them left in various languages we can analyze, and we still find some that were lost before then and found back again. The earliest written record we ever found was from the Loho language, the oldest member of the Mojhal language tree attested; the Mojhal tree has been itself linked to the Ñyqy tree some fifty years ago by the Pr Khorlan (3598).

Principles of Historical Linguistics

So, how does historical linguistics work? How does one know what the mother language of a bunch of other languages is? In historical linguistics, we study the similarities between languages and their features. If a feature is obviously common, there is a good chance it is inherited from a common ancestor. The same goes for words, we generally take the average of several words, we estimate what their ancestor word was like, and we estimate what sound change made these words evolve the way they did. If this sound change consistently works almost always, we know we hit right: sound changes are very regular, and exceptions are very rare. And this is how we can reconstruct a mother language that was lost to time thanks to its existing daughter languages.

But as we go back in time, it becomes harder and harder to get reliable data. Through evolution, some information is lost — maybe there once was an inflectional system that was lost in all daughter languages, and reconstructing that is nigh impossible. And since no reconstruction can be attested, we need a way to distinguish these from attested forms of words. This is why attested words are simply written like “this”, while reconstructed words are written with a preceding star like “*this”. Sometimes, to distinguish both from the text, you will see the word of interest be written either in bold or italics. This bears no difference in meaning.

On Proto-Languages

As we go back in time, there is a point at which we have to stop: we no longer find any related language to our current family, or we can’t find enough evidence that one of them is part of the family and if they are related, they are very distantly related. This language we cannot go beyond is called a proto-language, and it is the mother language of the current language family tree. In our case, the Proto-Ñyqy language, spoken by the Ñyqy people, is the mother language of the Ñyqy language family tree and the ancestor of the more widely known Mojhal languages.

There is something I want to insist on very clearly: a proto-language is not a “prototype” language as we might think at first — it is not an imperfect, inferior language that still needs some iterations before becoming a full-fledged language. It has been proven multiple times multiple times around the world, despite the best efforts of the researchers of a certain empire, that all languages are equally complex regardless of ethnicity, education, time, and place. Languages that are often described as “primitive” are either called so as a way to indicate they are ancient, and therefore close to a proto-language, or they are described so by people trying to belittle people based on incorrect belief that some ethnicities are somehow greater or better than others. This as well has been proven multiple times that this is not true. A proto-language bore as much complexity as any of the languages currently spoken around the world, and a primitive language in linguistic terms is a language close in time to these proto-languages, such as the Proto-Mojhal language (which is also in turn the proto-language of the Mojhal tree). The only reason these languages might seem simpler is because we do not know them and cannot know them in their entierty, so of course some features are missing from it, but they were surely there.

Note that “Proto-Ñyqy” is the usual and most widely accepted spelling of the name of the language and culture, but other spellings are accepted such as “Proto Ñy Qy”, “Proto Ñy Ħy”, “Proto Ḿy Qy”, or “Proto Ḿy Ħy”, each with their equivalent with one word only after the “Proto” part. As we’ll see later in Phonology: Consonants, the actual pronunciation of consonants is extremely uncertain, and each one of these orthographies are based on one of the possible pronunciations of the term *ñyqy. In this book, we’ll use the so called “coronal-only” orthography, unless mentionned otherwise. Some people also have the very bad habit of dubbing this language and culture as simply “Ñyqy” (or one of its variants), but this is very wrong, as the term “Ñyqy” designates the whole familiy of languages and cultures that come from the Proto-Ñyqy people. The Tiltinian languages are as much Tiltinian as they are Ñyqy languages, but that does not mean they are the same as the Proto-Ñyqy language, even if they are relatively close in terms of time. When speaking about something that is “Ñyqy”, we are generally speaking about daughter languages and cultures and not about the Proto-Ñyqy language and culture itself.

Note also we usually write this language with groups of morphemes, such as a noun group, as one word like we do with *ñyqy. However, when needed we might separate the morphemes by a dash, such as in *ñy-qy.

Reconstructing the Culture Associated to the Language

While the comparative method described in Principles of Historical Linguistics work on languages, we also have good reasons to believe they also work of culture: if elements of different cultures that share a language from the same family also share similar cultural elements, we have good reasons to believe these elements were inherited from an earlier stage of a common culture. This is an entire field of research in its own right, of course, but linguistics also come in handy when trying to figure out the culture of the Ñyqy people: the presence of certain words can indicate the presence of what they meant, while the impossibility of recreating a word at this stage of the language might indicate it only appeared in later stages of its evolution, and it only influenced parts of the decendents of the culture and language. For instance, the lack of word for “honey” in Proto-Ñyqy but the ability to reconstruct a separate word for both the northern and southern branches strongly suggests both branches discovered honey only after the Proto-Ñyqy language split up into different languages, and its people in different groups, while the easy reconstruction of *mygú signifying monkey strongly suggests both branches knew about this animal well before these two groups split up. More on their culture in Culture and People.